Basics of Finite Fields

In all the previous experiments, we dealt with codes over the binary alphabet. Codes can also be constructed over fields of size greater than . In this experiment, we shall focus on finite fields in general. Firstly, we will describe prime fields denoted by , where is a prime number. Then we study the construction of finite fields () of size , which is a power of a prime (, ). Then we describe the element through which every element of the finite field can be generated (primitive element) and the construction of minimal polynomials of all the elements.

The theory associated with Experiment-6 is divided into four parts:

- Prime Fields

- Ring of polynomials and Extended Euclidean algorithm

- Construction of finite fields of prime power

- Structural Properties of Finite Fields

- Vector space structure of finite fields

- Multiplicative structure of finite fields

- Minimal Polynomials

1. Prime Fields

Consider a set , where is prime. The addition and multiplication operations for any are defined as and . For simplicity of notation, we will use instead of and instead of subsequently in the theory.

We would like to argue that is a field. In Experiment-1, field definition is given. It is easy to verify the following field properties of :

- Closure under addition, multiplication

- Commutativity under addition, multiplication

- Distributivity with respect to addition and multiplication

- Additive identity is and multiplicative identity is

- Additive inverse of is

The only property which requires to be verified carefully is the existence of multiplicative inverse for every non-zero element in the field. In order to prove that, we need to invoke the fact that is prime. We also use the well-known relation of the greatest common divisor (), i.e., for integers and there are two integers and such that

Consider . is co-prime with as is a prime number. Hence, . Thus, there are two integers such that . Doing operation on the above relation, we have that . Thus, is the required multiplicative inverse of in the field .

Consider the case of . The addition and multiplication tables for are given below. For example, and . In this field, the additive inverse of an element is . For example, additive inverse of is . The multiplicative identity is in , so the multiplicative inverse of an element is if and only if . For example, the multiplicative inverse of is (check from Table 2). Students are suggested to find the multiplicative inverses of all the elements from Table 2 and additive inverses of all the elements from Table 1.

Table 1: Addition table for

Table 2: Multiplication table for

2. Ring of Polynomials and Extended Euclidean Division Algorithm

In Experiment-1, we have defined the field . Students are suggested to recall the axioms that satisfy with two binary operations called addition and multiplication (see Section 1 in the current experiment). Let be a set of elements, known as a ring, which satisfies all the field axioms but does not necessarily require the presence of multiplicative inverses and doesn't require satisfying the commutative property with respect to multiplication. It is denoted by . Consider the set of all polynomials with coefficients from , denoted by where is indeterminate. It is easy to verify that is a ring of polynomials. Addition and multiplication are defined as ordinary addition and multiplication, with the difference being the coefficient operations are carried out .

For example, consider the ring of polynomials . Let and , then we have that

We also can compute the product of and as follows:

Let and are the two polynomials in . The division of by is computed as follows:

![Division of polynomials in F7[x]](./images/exp6-fig2.png)

Division algorithm for polynomials states that there is a unique representation for and in ( is a field), , where the degree of is less than the degree of . Throughout the experiment, we denote the degree of any polynomial, say by . Sometimes it is convenient to express the remainder polynomial in terms of the modulo operation, as we do for integers, i.e., . Using the division algorithm repetitively, the of two polynomials is determined, which is discussed below.

Euclidean Algorithm: To compute the , the division algorithm is used repetitively. Repeated application of the division algorithm, we obtain a series of equations:

Then , the last nonzero remainder of the division process. Let's understand the procedure to find the of two polynomials with the following example.

Example 1:

Consider the polynomials and from . Remember that all the operations are performed modulo 2. We will apply the Euclidean algorithm to find the .

![Division of polynomials in F2[x]](./images/exp6-fig3.png)

Therefore by applying the division algorithm for the polynomials and we get

Here, quotient and the remainder .

Step 2:

Next, we apply division algorithm for the polynomials and we get

Here, quotient and the remainder .

Step 3:

Next, we apply division algorithm for the polynomials and we get

Since the remainder , the Euclidean algorithm terminates here, and the last non-zero remainder is . Therefore .

The relation of the greatest common divisor of two polynomials is analogous to integers. For any two polynomials and , there exists polynomials and such that

In further discussion, we always consider is the dividend and is the divisor. The relation above is used to find the construction of finite fields of prime power (also called Galois fields) and is described in Section 3. The well-known extended Euclidean Algorithm for polynomials for finding and is given below. In this algorithm, the remainder and the quotient determined at the th step of the Euclidean algorithm are used.

Extended Euclidean Division Algorithm:

The polynomials and are computed by finding intermediate polynomials and satisfying

at every step of the algorithm. The quotient obtained at the th step of the Euclidean algorithm is used to update and :

for (until termination), with

We have seen that the last non-zero remainder obtained in the Euclidean algorithm is the . So, the extended Euclidean algorithm terminates when the last non-zero remainder is expressed as above. The corresponding and resulted as and of the . In the following example, we determine the polynomials and for Example 1.

Example 2:

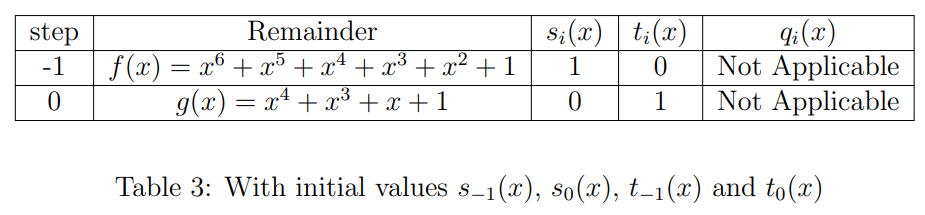

Consider Example 1. We have obtained . A series of equations obtained in the Euclidean algorithm are used sequentially to determine the and . We start with the initial values given above, and tabulated in Table 4.

Table 3: Initial values for Extended Euclidean Algorithm

We will apply the extended Euclidean algorithm step by step till we get the remainder zero.

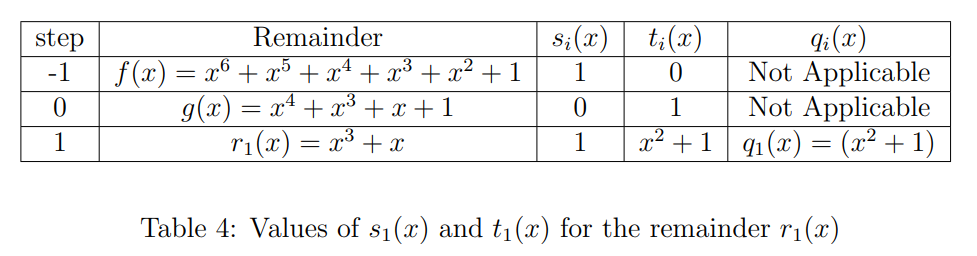

Step 1:

At this step we determine and . For this, we need the quotient obtained at the first step of the Euclidean algorithm, and the initial values from the above table. From the update equations:

At the first step of the Euclidean algorithm, the remainder is . Students are suggested to verify that . Table 5 shows all the values that have been obtained till now.

Table 4: Values after Step 1 of Extended Euclidean Algorithm

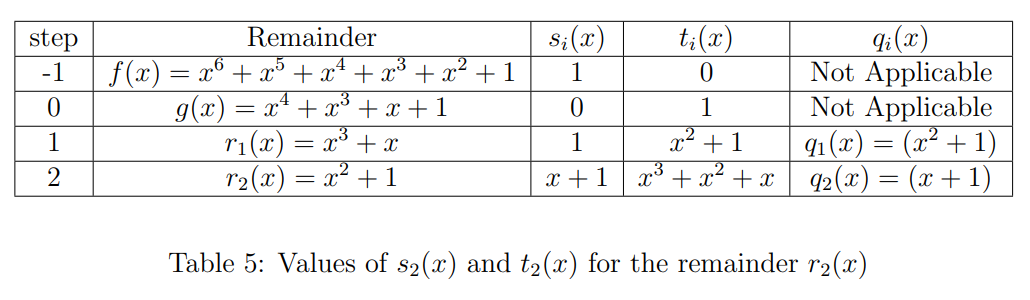

Step 2:

As done in Step 1, at this step we determine and . For this we need the values obtained in Table 5 and the quotient obtained in step 2 of the Euclidean algorithm. From the update equations:

At this step, the remainder is . Table 6 shows all the values obtained till now. Students are encouraged to confirm that .

Table 5: Values after Step 2 of Extended Euclidean Algorithm

Note that the Euclidean algorithm for this example terminates here, since , and the . Therefore the extended Euclidean algorithm also terminates here, and . That is,

Hence for this example the polynomials and . From the previous step we know the remainder and the quotient . Hence with all these values we obtain the final table of the algorithm (Table 7):

Table 6: Final values of Extended Euclidean Algorithm

3. Construction of Finite Fields

In this section, we provide fundamental definitions necessary for building finite fields. These definitions are essential for the construction process.

Monic Polynomial:

Consider a polynomial of degree , given by . is said to be monic if .

Irreducible Polynomial:

A monic polynomial over of degree is said to be irreducible if it cannot be factored into the form:

where .

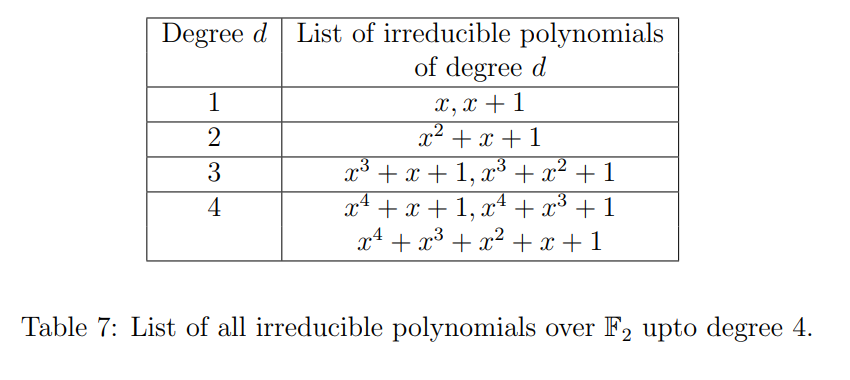

Consider a binary field with and . The list of all irreducible polynomials over up to degree 4 are given in the table below:

Table 7: Irreducible polynomials over up to degree 4

It can be shown that for every prime , and every integer , irreducible polynomials of degree exist. Consider the set , where is irreducible of degree . is the collection of equivalence classes. Where we define

which means is a multiple of . Each equivalence class represents an element in the finite field. These equivalence classes can be denoted as , where is a representative polynomial within that class. This class includes all the polynomials whose division by gives the remainder . For simplicity of notation, the element is represented as . From this, we can see that the field is the collection of all the polynomials of degrees less than or equal to . It is easy to verify the field properties (see Section 1) of . Students are encouraged to verify all the field properties carefully. The critical thing to verify is that every nonzero element in the field has another element with which you can multiply it to get 1 (the multiplicative inverse) which is discussed below.

Consider any non-zero element from the field . Since is the irreducible polynomial of degree , the . From the previous section, there are two polynomials and such that . By performing a modulo operation with the irreducible polynomial , we get . Thus is the multiplicative inverse of in the field .

For example, consider irreducible polynomial over . Then . In this, each element is an equivalence class. Consider an element from , this class includes all polynomials over which gives the remainder with modulo . In this field, the multiplicative inverse of is , since .

4. Structural Properties of Finite Fields

4.1 Vector Space Structure of a Finite Field

Consider a finite field with elements. The characteristic of is the smallest integer such that in . Hence, contains the set .

The arithmetic used to operate on these elements is arithmetic since in . It can be shown that the characteristic is a prime. Hence, contains a copy of . It can be shown that if and are fields and , then is a vector space over . It follows that is a vector space over . Let be the dimension of this vector space over . Then, we have

where is a basis of over . It follows that is of size . Thus, every finite field has size of the form , prime, (moreover is the characteristic of ).

For example, consider . The basis of over is and is the vector space spanned by the set over which has size .

4.2 Multiplicative Structure of a Finite Field

We denote . The multiplicative order of is the smallest exponent such that . Every finite field contains an element of order . In terms of , has the representation

An element of order is called a primitive element of . Multiplicative inverse of any () is , since .

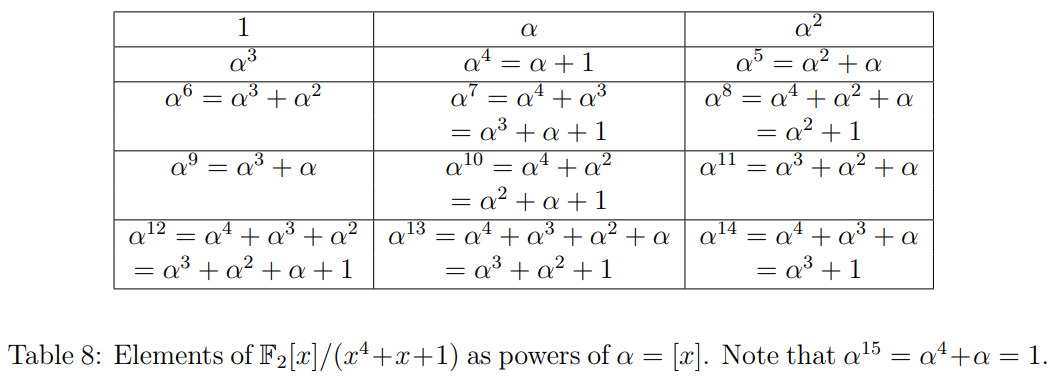

For example, consider . Note that is irreducible over . Denote , the equivalence class of in . Alternately, we may regard as the imaginary element satisfying . Now, we will show that we can express all the non-zero elements of as powers of (see Table 9). In Table 9, we get an element by multiplying the previous element by and then applying the condition . We also use the condition every element is its own additive inverse. This is because the characteristic of the field is . For example, let's calculate the polynomial representation of ,

In this field, the multiplicative inverse of any () is , since . For example, multiplicative inverse of is .

Table 8: Powers of in

As a part of the study of finite fields, we will discuss the construction of minimal polynomials, which are useful in constructing codes that we will discuss in Experiment 9.

4.3 Minimal Polynomials

The minimal polynomial of is the smallest degree monic polynomial in of which is a zero. Some properties of the minimal polynomial (without proofs) are given below:

- is an irreducible polynomial.

- If , then , i.e., if is a root of , then divides .

- Applying the above fact, we have that . This is because all the elements of field satisfy the equation .

- For a non-zero element , all the distinct elements of , where is the characteristic of , are all termed as conjugates of the element . Let denote the set of all conjugates of the element including itself.

- . In particular, an element and all its conjugates have the same minimal polynomial.

Example 3:

Consider the Galois field such that (see Table 9). Suppose we want to determine the minimal polynomial of in . Recall that conjugates of are the distinct elements , where is the characteristic of (here ). So the conjugates of the element are and . Hence, the minimal polynomial of is