State Diagrams

Finite State Machines and Sequential Circuits

There are many applications where there is a need for our circuits to have "memory"; to remember previous inputs and calculate their outputs according to them. A circuit whose output depends not only on the present input but also on the history of the input is called a sequential circuit. In this section, we will learn how to design and build such sequential circuits using finite state machines (FSMs).

Understanding Sequential vs. Combinational Circuits

Combinational Circuits: Output depends only on current inputs Sequential Circuits: Output depends on current inputs AND previous states (memory)

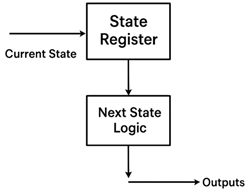

A finite state machine is a mathematical model used to design sequential circuits. As shown in Figure 1, an FSM consists of:

- State Register: Stores the current state using flip-flops

- Next State Logic: Combinational circuit that determines the next state

- Output Logic: Combinational circuit that generates outputs

State Diagram Fundamentals

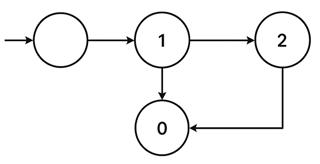

A state diagram is a graphical representation that describes the behavior of a finite state machine. As illustrated in Figure 2, every component of a state diagram has a specific meaning:

State Diagram Components

States (Circles): Each circle represents a unique condition or state of the machine

- Upper half: Contains the state name or description

- Lower half: Contains the output value for that state

Transitions (Arrows): Each arrow represents a possible change from one state to another

- Arrow label: Shows the input condition that causes the transition

- Transition timing: Occurs on each clock cycle based on current input

Initial State: Usually marked with an arrow pointing to it from nowhere, representing the starting condition

Design of 11011 Sequence Detector Using JK Flip-Flops (With Overlap)

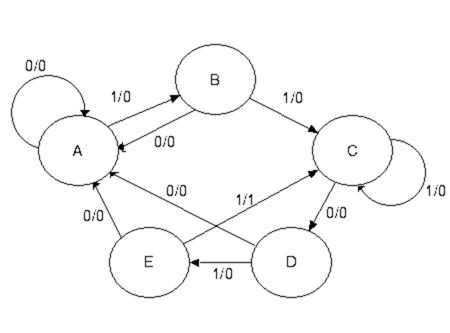

Step 1 – Derive the State Diagram and State Table

Step 1a – Determine the Number of States

For a sequence detector detecting an N-bit sequence, at least N states are required.

We are designing a 5-bit sequence detector (11011), therefore the number of states required is 5.

Label the states as A, B, C, D, and E.

A is the initial state.

Step 1b – Characterize Each State

| State | Has | Awaiting |

|---|---|---|

| A | — | 11011 |

| B | 1 | 1011 |

| C | 11 | 011 |

| D | 110 | 11 |

| E | 1101 | 1 |

Step 1c – Transitions for Expected Sequence

Transitions are labeled as X / Z, where:

- X = Input

- Z = Output

For the expected input sequence:

- A → B on 1 / 0

- B → C on 1 / 0

- C → D on 0 / 0

- D → E on 1 / 0

- E → C on 1 / 1 (sequence detected, overlapping allowed)

Step 1d – Inputs That Break the Sequence

| State | On Input 0 | On Input 1 | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Stay in A | Go to B | Waiting on 1 |

| B | Go to A | Go to C | "10" not part of sequence |

| C | Go to D | Stay in C | Overlap due to “11” |

| D | Go to A | Go to E | "1100" restarts sequence |

| E | Go to A | Go to C | "11011" detected, overlap at "11" |

Step 1e – Generate State Table with Output

| Present State | Input X | Next State | Output Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0 | A | 0 |

| A | 1 | B | 0 |

| B | 0 | A | 0 |

| B | 1 | C | 0 |

| C | 0 | D | 0 |

| C | 1 | C | 0 |

| D | 0 | A | 0 |

| D | 1 | E | 0 |

| E | 0 | A | 0 |

| E | 1 | C | 1 |

Step 2 – Determine Number of Flip-Flops

We have 5 states (N = 5).

To determine the number of flip-flops:

2^(P-1) < 5 ≤ 2^P → P = 3

Therefore, three flip-flops are required.

Step 3 – Assign State Codes

Optimized state assignments:

| State | Binary Code (Y₂ Y₁ Y₀) |

|---|---|

| A | 000 |

| B | 001 |

| C | 011 |

| D | 100 |

| E | 101 |

Step 4 – Transition Table with Output

| Y₂Y₁Y₀ (PS) | X | Next State (Y₂'Y₁'Y₀') | Z |

|---|---|---|---|

| 000 (A) | 0 | 000 | 0 |

| 000 | 1 | 001 | 0 |

| 001 (B) | 0 | 000 | 0 |

| 001 | 1 | 011 | 0 |

| 011 (C) | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 011 | 1 | 011 | 0 |

| 100 (D) | 0 | 000 | 0 |

| 100 | 1 | 101 | 0 |

| 101 (E) | 0 | 000 | 0 |

| 101 | 1 | 011 | 1 |

Step 4a – Output Equation

The output Z = 1 only when:

Present State = 101 (Y₂=1, Y₁=0, Y₀=1) and Input X = 1

Therefore,

Z = X · Y₂ · Y₁' · Y₀

Step 5 – Separate Transition Tables (per Flip-Flop)

From D flip-flop behavior, the next-state equations are:

D₂ = X’·Y₁ + X·Y₂·Y₀’

D₁ = X·Y₀

D₀ = X

Step 6 – Use JK Flip-Flops

The design specifies JK flip-flops, so D equations are converted into JK excitation forms.

Step 7 – JK Excitation Table

| Q(T) | Q(T+1) | J | K |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | d |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | d |

| 1 | 0 | d | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | d | 0 |

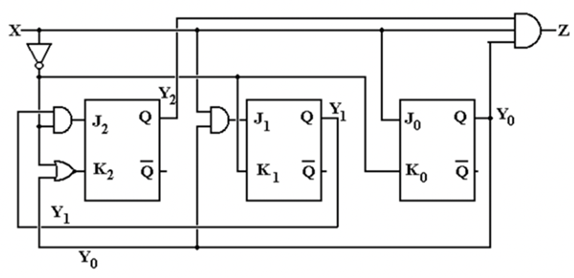

Step 8 – Derive Input Equations

Flip-Flop Y₂

- For X = 0 → J₂ = Y₁, K₂ = 1

- For X = 1 → J₂ = 0, K₂ = Y₀

Combined equations:

J₂ = X’·Y₁

K₂ = X’ + Y₀

Flip-Flop Y₁

- For X = 0 → J₁ = 0, K₁ = 1

- For X = 1 → J₁ = Y₀, K₁ = 0

Combined equations:

J₁ = X·Y₀

K₁ = X’

Flip-Flop Y₀

- For X = 0 → J₀ = 0, K₀ = 1

- For X = 1 → J₀ = 1, K₀ = 0

Combined equations:

J₀ = X

K₀ = X’

Step 9 – Final Equations Summary

| Parameter | Equation |

|---|---|

| Z | Z = X·Y₂·Y₁'·Y₀ |

| J₂ | J₂ = X'·Y₁ |

| K₂ | K₂ = X' + Y₀ |

| J₁ | J₁ = X·Y₀ |

| K₁ | K₁ = X' |

| J₀ | J₀ = X |

| K₀ | K₀ = X' |

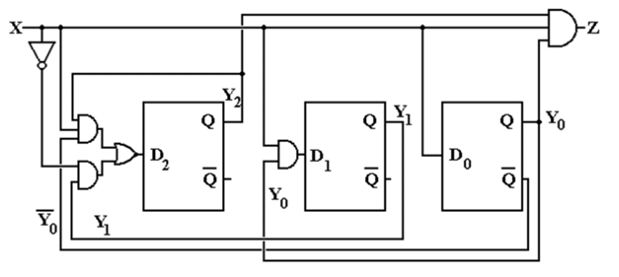

Step 10 – Circuit Representation

The circuit shown above represents the Finite State Machine (FSM) implementation using three JK flip-flops, designed according to the state and output equations derived previously. For practical implementation, logic gates corresponding to each equation are connected to drive the J and K inputs of the flip-flops, and the output Z is derived from the condition Z = X·Y₂·Y₁'·Y₀.

Equivalent D Flip-Flop Implementation

If implemented using D flip-flops, the equivalent next-state equations are:

D₂ = X'·Y₁ + X·Y₂·Y₀'

D₁ = X·Y₀

D₀ = X

Types of Finite State Machines

Moore State Machine

In a Moore machine (Figure 12a), the output depends only on the current state:

Output = f(Present State)

Characteristics:

- Outputs are stable and change only on state transitions

- Generally requires more states for complex problems

- Outputs are synchronized with the clock

- Less susceptible to input noise

Mealy State Machine

In a Mealy machine (Figure 12b), the output depends on both current state and current inputs:

Output = f(Present State, Inputs)

Characteristics:

- Outputs can change immediately when inputs change

- Generally requires fewer states than Moore machines

- Faster response to input changes

- May produce glitches if inputs change between clock edges

Applications of Finite State Machines

FSMs are fundamental building blocks in digital systems:

Control Units

- Processor control: Instruction fetch, decode, execute cycles

- Memory controllers: DRAM refresh, cache management

- Communication protocols: Handshaking, error detection

Sequential Detectors

- Pattern recognition: Detecting specific bit sequences

- Security systems: Password verification, access control

- Communication: Frame synchronization, protocol parsing

Counters and Timers

- Digital clocks: Time keeping, alarm systems

- Traffic controllers: Light sequencing, timing control

- Industrial automation: Process control, machinery operation

The systematic design procedure we've covered provides a reliable method for implementing any sequential logic function using finite state machines, making them indispensable tools in digital system design.