Virtual experiments to study characteristics of plant cells and genomes

Theory

Definition of Genome

The term “genome” was introduced by Winkler at the beginning of the 20th century to designate a haploid set of chromosomes with their genes. The genome is the entire set of DNA instructions found in a cell. In humans, the genome consists of 23 pairs of chromosomes located in the cell’s nucleus, as well as a small chromosome in the cell’s mitochondria. A genome contains all the information needed for an individual to develop and function.

Importance of studying plant genomes

Plants are essential for life on Earth. Hence, studying their genomes is very important. Plant genome research helps us understand the huge variability that is there in the plant kingdom. Many plants might become extinct before we even discover them. This means we could lose important genes and information about how plants can be used. For most plant species we do not yet have even the basic information like chromosome counts and the genetic make-up. This lack of knowledge limits our ability to use plants for breeding and environmental purposes. To address these gaps, international efforts are being made, such as the Royal Botanic Gardens' workshop and the Millennium Seed Bank project. This Seed Bank project aims to collect and preserve seeds from many plant species, ensuring we protect plant genetic diversity for the future.

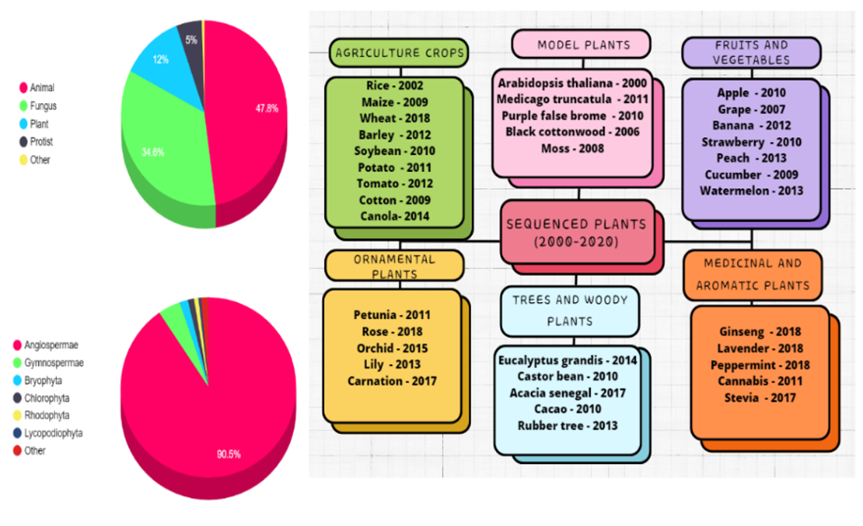

Fig 1. Plant species sequenced since 2000-2020

Difference between Animal and plant genome:

Plant and animal genomes exhibit significant differences in their structure, function, and evolutionary processes. Plant genomes are often larger and more variable in size. They range from small genomes (~135 Mb of Arabidopsis thaliana) to the large genomes (such as that of wheat which is ~17 Gb). Polyploidy, a condition with multiple sets of chromosomes, is frequently observed. In contrast, the animal genomes are typically more uniform in size. The human genome is approximately 3.2 Gb in size. Polyploidy is relatively rare in animal genomes.

Plants possess three distinct genomes—the nuclear, chloroplast, and mitochondrial genome. Animals have only nuclear and mitochondrial genomes lacking the chloroplast genome unique to plants. Additionally, plant genomes have lower gene density due to larger intergenic regions and a higher proportion of repetitive DNA compared to animal genomes. Plants frequently undergo gene duplication and polyploidy, contributing to genetic diversity and adaptability, whereas animals rely more on point mutations and recombination. Understanding these differences enhances our knowledge of the distinct evolutionary paths and functional organisation in plants and animals.

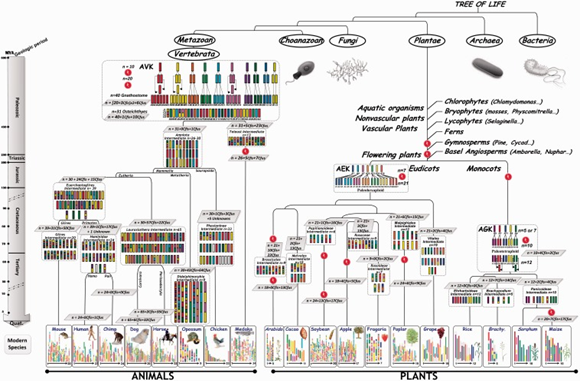

Fig 2. Comparison of Plant and animal genomes

Uniqueness of Plant Genomes:

- Nuclear Genome:

The nuclear genome is the largest and most complex part of a plant’s genetic material, containing most genetic information. Genome sizes vary widely among plants, ranging from about 63 Mb in Genlisea aurea (a carnivorous plant species) to over 149 Gb in Paris japonica and more recently Tmesipteris oblanceolate (a fork fern) with 160 billion base pairs.

- Plant nuclear genomes have evolved through polyploidy (duplication of the entire genome), horizontal gene transfer, and gene loss.

- Encodes most of the plant's functional genes, including those responsible for growth, development, and response to environmental stresses.

- rovides the genetic basis for traits utilized in agriculture and horticulture, such as yield, disease resistance, and flower morphology.

Examples: Arabidopsis thaliana (Common name: Thale cress, mouse ear cress) of the mustard family is a model organism with a small and well-studied genome. Wheat (Triticum aestivum) is an example of a large, complex nuclear genome.

- Chloroplast Genome:

The chloroplast genome (cpDNA) is a small, circular DNA molecule found in chloroplasts, typically ranging from 120 to 160 kb in size. It encodes around 110-120 genes related to photosynthesis and other chloroplast functions.

- Derived from a cyanobacterial ancestor through endosymbiosis.

- Exhibits conserved structure and gene order across most plant species, but some variations occur due to rearrangements and gene losses.

- Essential for photosynthesis, the process by which plants convert light energy into chemical energy.

- It is used in plant systematics and evolutionary studies due to its relatively slow mutation rate.

Examples:

- Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum): Its chloroplast genome was among the earliest to be sequenced.

- Spinach (Spinacia oleracea): Its chloroplast genome sequencing has offered detailed insights into the evolution, gene organization, and regulatory mechanisms of photosynthetic machinery.

- Mitochondrial Genome:

The mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) is also circular but much larger and more variable in size than the chloroplast genome. It contains genes essential for cellular respiration and energy production, typically fewer than 50 protein-coding genes.

- Originated from an alpha-proteobacterial ancestor through endosymbiosis.

- Characterized by high rates of rearrangement and gene transfer to the nuclear genome, leading to considerable size variation.

- Vital for ATP production through oxidative phosphorylation.

- Plays a role in cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS), which is utilized in hybrid seed production.

Examples: Maize (Zea mays): Its mitochondrial genome studies reveal complex structural rearrangements. Rape (Brassica napus): Used to study CMS and its role in hybrid breeding.

- Model Genomes:

- Arabidopsis thaliana: A small flowering plant commonly used in plant biology research due to its short life cycle and small genome size.

- Oryza sativa (rice): A staple food crop with a fully sequenced genome, making it a valuable model for cereal crops.

- Zea mays (maize): Another important cereal crop with a complex genome, serving as a model for understanding crop genetics and evolution.

Genomic Plasticity

Genomic plasticity refers to the ability of an organism’s genome to undergo changes that can result in variations in gene content, gene expression, genome structure, and chromosome number. In plants, this plasticity allows for adaptation to diverse and changing environments, influencing traits such as growth, reproduction, and stress resistance.

Reasons for Genomic Plasticity:

Polyploidy: Many plants have undergone whole-genome duplication events, resulting in multiple copies of their entire genome. This can lead to increased genetic diversity and adaptive potential.

- Example: Wheat (Triticum aestivum)

- Nature: Hexaploidy species containing genomes from three different ancestors (A, B and D genomes).

- Significance: Polyploidy has provided a broad genetic base, allowing wheat to possess traits such as disease resistance and adaptation to diverse environments.

- Details: The polyploid nature of wheat enables it to retain beneficial genes from each progenitor species and facilitates the evolution of new traits due to the presence of multiple gene copies.

Transposable Elements (TE): These mobile genetic elements contribute to genome plasticity by moving around within the genome, potentially causing mutations and influencing gene expression.

- Example: Maize (Zea mays)

- Nature: TEs make up a large portion of the maize genome (~85%).

- Significance: TEs contribute to genetic diversity, gene regulation, and evolution of new traits.

- Details: Active TEs can move within the genome, causing insertions, deletions, and rearrangements that can alter gene expression and create novel genetic combinations.

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) involves the transfer of genetic material between different species, bypassing traditional inheritance. HGT can introduce new genes and functions into a plant genome, contributing to adaptability and survival in diverse ecological niches.

- Example: Sweet Potato (Ipomoea batatas)

- Nature: Acquisition of Agrobacterium genes.

- Significance: HGT has integrated bacterial genes into the sweet potato genome, which are believed to confer certain growth advantages.

- Details: The integration of Agrobacterium T-DNA into the sweet potato genome is a rare example of HGT in plants, potentially contributing to tuber formation and other agronomically important traits.

Applications:

Crop Improvement and Breeding:

- Example: Genomic selection in crops like maize and wheat allows breeders to predict and select desirable traits, speeding up the breeding process and improving yield, disease resistance, and climate resilience.

- Importance: This accelerates the development of new varieties that are better suited to changing environmental conditions and can support food security.

Pharmaceuticals and Bioengineering:

- Example: Genomic studies of plants like the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) are crucial for producing pharmaceutical compounds such as morphine.

- Importance: Plant genomics facilitates the engineering of plants or microorganisms to produce medicinal compounds, reducing reliance on natural extraction.

Environmental Sustainability:

- Example: Genetically engineering plants like poplar (Populus spp.) for enhanced biofuel production.

- Importance: Helps in developing sustainable biofuels and mitigating climate change by providing renewable energy sources.

Golden Rice: A Pioneering Example of Plant Genome Engineering

Species: Oryza sativa L. (Asian rice)

Genetic Modification: GR2E (Golden Rice 2 Event E)

Description: Golden Rice (Oryza sativa L., GR2E) has been genetically modified to synthesize beta-carotene, which serves as a precursor to vitamin A, within the consumable portions of rice grains. The primary goal is to combat widespread vitamin A deficiency in regions where rice is a dietary staple. The deficiency is associated with significant health risks such as vision impairment, compromised immunity, and higher mortality rates, especially impacting children and pregnant women.

Importance:

Addressing Vitamin A Deficiency:

- Context: Vitamin A deficiency is a major public health issue, especially in developing countries. It affects millions of children, leading to blindness, immune deficiencies, and increased mortality.

- Application: Golden Rice is designed to combat the deficiency by providing a dietary source of vitamin A. The genetic modification involved introducing genes from maize and a bacterium (Erwinia uredovora) into the rice genome to enable the rice plant to produce beta-carotene in its endosperm (the edible part of the rice grain).

Golden Rice serves as a prototype for biofortified crops aimed at improving public health through genetic enhancements. Its development underscores the role of plant genomics in addressing complex nutritional and agricultural challenges by providing targeted solutions that traditional breeding methods cannot achieve as efficiently.

Technological Advances:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Example: Sequencing of the Arabidopsis thaliana Genome

- Reason: NGS technology has drastically reduced the time and cost of sequencing entire genomes, allowing researchers to sequence multiple plant species and individuals efficiently.

- Information: Arabidopsis thaliana was one of the first plant genomes sequenced using NGS, providing a comprehensive reference genome that serves as a model for understanding plant genetics and biology. This sequencing revealed the structure, function, and evolution of genes in a plant model.

Genome Editing:

Example: Development of Disease-Resistant Crops

- Reason: CRISPR-Cas9 allows precise, targeted modifications in the plant genome, enabling the creation of crops with improved traits such as disease resistance, drought tolerance, and enhanced nutritional content.

- Information: CRISPR-Cas9 has been used to develop disease-resistant rice by knocking out the susceptibility gene OsSWEET14, which reduces susceptibility to bacterial blight.

Synthetic Biology

Example: Synthetic Pathways for Biofuel Production

- Reason: Synthetic biology enables the design and construction of new biological parts, devices, and systems, allowing the creation of plants with novel metabolic pathways and enhanced capabilities.

- Information: Researchers have engineered plants with synthetic pathways to produce biofuels and bioplastics, using techniques to insert and optimize pathways to produce valuable chemicals.