An introduction to Next Generation Sequencing (NGS)

Introduction

Whole genome sequencing in humans defines the process involved in a laboratory environment for determining millions of nucleotides of a complete DNA sequence including non-coding regions. Apart from existing molecular biology techniques such as microarray methods for DNA sequencing, recent advances in technology relies on sequence-based approaches for determining the nucleic acid sequence of a given DNA or cDNA molecule. It has been noted that the field of DNA sequencing technology and development has diverse history and massively many DNA sequencing platforms are readily available to reduce the cost of existing DNA sequencing methods. After the clear understanding of the structure of a DNA molecule and its bases by Watson and Crick’s findings, Sanger sequencing (“first-generation sequencing”) method was employed to sequence the first human genome in the Human Genome Project (HGP) and successively used for large-scale DNA sequencing projects. Frederick Sanger sequenced the entire genome of the virus phiX174 9 (single-stranded DNA virus that infects Escherichia coli). When compared to conventional methods of sequencing using capillary electrophoresis, the emergence of next-generation sequencing (NGS) (deep sequencing) have paved path for new challenges and possibilities in biological and clinical applications for exploring genomes with more accurate and reliable sequencing information. NGS can sequence hundreds and thousands of genes or whole genome within a short duration and offers wider opportunities in diagnostics for providing personalized medicine.

Theory

DNA sequencing methods have revolutionized life-science research that shifts genomics paradigms for addressing biological questions at a genome scale and had greater impact in various research. There exists many researches to sequence DNA molecule after Fredrick Sanger and colleagues’ proposed chain-termination method for DNA sequencing. In Sanger sequencing, at first a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) is denatured into two single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). A DNA primer complementary to the template DNA (the DNA to be sequenced) is the region for DNA synthesis. The polymerase functions to extend the added primer by adding the complementary dNTP to the template strand. Four polymerase solutions with four types of dNTPs ( A, G, C, T) but only one type of ddNTP are added. For terminating the synthesis of DNA, four dideoxynucleotide triphosphates ( ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, and ddTTP, oxygen atom removed from the ribonucleotide) labelled with fluorescent dye are used to terminate the synthesis reaction and this cannot form a link with the next nucleotide resulting in termination of the process. DNA fragments are then converted to ssDNA by denaturation. Reaction products, denatured fragments of DNA are subjected to gel electrophoresis, fragments get separated according to their sizes and the sequence of the DNA is thus determined.

With the demand of sequencing of large amounts of genomic DNA, next generation sequencing approaches are now possible to sequence an entire human genome. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies or high-throughput sequencing are new modern sequencing methods to sequence DNA and RNA molecule. NGS are alternative approaches to older technologies such as PCR with Sanger sequencing, electrophoresis, hybridization, and real-time product detection in genome analysis. NGS has several applications over Sanger sequencing: Cost effective, more accurate and reliable sequencing data, and reduced time period for sequencing, that is sequencing in a few days, for a few thousand dollars. With these marked advantages, NGS has become a powerful tool in genome research and clinical applications. The data derived from sequencing technologies can further be used for in-depth gene family analysis a better approach to identify evolutionary history of gene families. Basically, the principle behind NGS) is similar to Sanger Sequencing, capillary electrophoresis where the genomics strand is fragmented to bases and each fragments are identified by emitted signals upon ligation of the fragments against a template strand.

The entire NGS can be explained in four steps: sample extraction, library preparation, sequencing, and analysis.

1. Sample Extraction (DNA fragmentation)

In order to prepare RNA or DNA for NGS analysis, the basic steps to follow are

• Fragmentation of targeted sequence into short segments of desired length (100–300 bp). The size of the target DNA fragments is a key element for NGS library construction.

• Converting targeted sequence to double-stranded DNA

• Attachment of oligonucleotide adapters to target fragments ends

• Quantification of the final library product for sequencing.

Many methods are available to fragment nucleic acid chains such as physical, enzymatic, and chemical methods. Physical methods such as acoustic shearing and sonication break DNA into short segments. There are general considerations for nucleic acid isolation for NGS which included yield (Nanograms (ng) to micrograms (µg) of DNA or RNA), purity (the isolated component must be free of compounds that can inhibit enzymes during library preparation, and Quality (integrity of isolated nucleic acids). The isolated nucleic acid purity is typically expressed as an A260/280 value which can be determined by spectrophotometer. Using hybridization capture assay, the short segments of nucleotides which are relevant to the targeted DNA sequences are pulled out with specific complementary probes. In amplicon assay, pairs of primes are used to amplify targeted DNA sequence. These DNA segments are then used for library preparation.

2. Library Preparation

The next step after isolation and purification of nucleic acids is the library preparation, a process for modifying DNA segments. Steps included amplification of the targeted sequence to form a pool of DNA segments and addition of sequencing adapters to interact with NGS platform. Adapters are basically oligonucleotides with sequences complimentary to the sequence of interest. The adapter ligated ends of nucleic acids are used for enabling sequencing. Adapters are oligonucleotides with sequences that are complementary to the priming oligo’s on the sequencing chips. The ends of the nucleic acid fragments are ligated with adapters (commonly known as P5 and P7) to enable sequencing. In case of RNA as the targeted sequence, RNA must be first converted to cDNA by reverse transcription. Such modification allows the primers to bind to DNA segments which are enabled for massive parallel sequencing. After preparing the library, it must be quantified to perform sequencing of required concentration of molecules. The common methods for library quantification is fluorescence spectroscopy and real-time PCR.

3. DNA sequencing

Massive parallel sequencing is the basics factor employed in NGS sequencer. The pooled library is uploaded onto a NGS sequencer which reads the nucleotides one by one. Sequencing matrices may differ with types of sequencers. Number of reads produced depends on the type of sequencing platform and kit used. Illumina NGS sequencer, most relevant and successful sequencing technology uses flow cells while Ion Torrent NGS sequencer uses sequencing chips. The uploaded library fragment get hybridized to the primer that amplifies for producing cluster of clones. Fluorescently labelled nucleotides produce complementary strand for each fragment and the addition of each tagged nucleotide records the fluorescent emission and its wavelength and intensity are marked to identify sequence templates.

4. Bioinformatics based Alignment and Data Analysis

After sequencing, the next step is to use specialized software packages to analyse the recorded data. Bioinformatics tools aid in converting raw sequencing data into meaningful results. Bioinformatics processes in NGS includes base calling, read alignment, variant identification, and variant annotation. The sequence information were compared to human genome sequence as reference for identifying presence of variations such as diseases or mutations in the targeted sequence of interest.

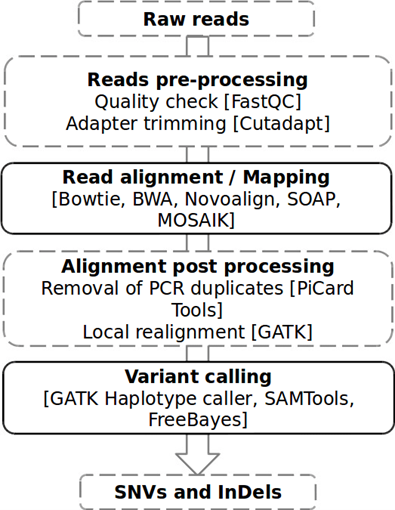

Pipelines in next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis

Systematic and automated workflows for processing the raw sequencing data through several interconnected steps for getting meaningful results are generally referred to as pipelines in next-generation sequencing. Depending on specific research goals and preferences researchers often customize their pipelines for NGS data analysis.

Common steps that follow in Next-generation Sequencing (NGS) are:

1. Quality Control (QC): This step is the crucial step in next-generation sequencing which assesses the quality of raw sequencing data. It identifies and removes low-quality reads, improving the accuracy and reliability of NGS experiments. During sequence read quality assessment, a quality score, termed Phred score, has been assigned to each nucleotide in the raw sequence. The highly consistent sequence has high Phred scores and vice versa. FastQC or NGS-QC Generator are commonly used tools for generating the quality reports of the provided data and for visualizing the quality scores of the entire given dataset. This removes any low-quality sequence reads and/or portions of reads and output is the “cleaned” FASTQ file. The raw data analysis was based on image processing and base calling. Usually FASTQ format is employed for storing raw biological sequence data which is a standard text-based format, standard for storing the output of high throughput sequencing instruments. It stores corresponding scores of a sequence of interest. After identifying the quality of bases, the low-quality bases, that relates to adapter contamination can be filtered or trimmed from the data set. The steps include trimming adapters, and de-duplication of reads to remove repeat reads of the library fragments and reads of PCR amplicons of the same sequence. Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or BBDuk are examples of tools for trimming and filtering. PCR duplicates produced during library preparation and sequencing may lead to unbiased results due to the overrepresentation of certain bases in the sequence. Picard or SAM tools can be used to remove duplicates. The read lengths were analyzed completely before starting the downstream analysis. GC content analysis, Kmer content analysis that produces short subsequences of a fixed length (k) in the raw sequence reads, for example, a sequence ACGTGCTAG split into "ACGT," "CGTG," "GTGC," "TGCT," "GCTA as overlapping or non-overlapping subsequences as Kmer for data quality analysis, Error Profile Analysis for identifying sequence errors and phasing analysis for analyzing reads with paired-end reads or reads with overlapping ends that accuracy of the process.

A FASTQ files consist of a set of reads, with each read having 4 lines of data.

It begins with a '@' character. The second line contains only raw nucleotide sequence which is denoted by a sequence identifier (the base calls; A, C, T, G and N) that represents a sequence identifier or the metadata line. The values on this line depends on the sequencing platforms and the sequence database. Next is a separator, which is a plus (+) sign. It separates between the determined base pair sequence and the subsequent specifically known as quality string. Next is the Quality strings that are sequence including alphanumerical characters that codes for a probability value known as Phred quality score, which ranges in general anywhere from 0 to infinity. Phred quality score represents the quality nucleobases generated by automated DNA sequencing.

2. Read Alignment: This step involves mapping the short sequence reads produced by the NGS platforms to another reference genome or transcriptome, which is a well-annotated sequence. It helps in understanding genetic variations, gene expression levels, and other biological features of the given sequence.In this step, mapping of each base call to its corresponding location in the genome is performed. Reference genomes and transcriptomes are used for alignment tools for NGS community. The alignment process or algorithms identifies the origin of the reads in the reference by comparing the short reads to the reference sequence and determines their best match. Examples of alignment algorithms include Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA), Bowtie, STAR (Spliced Transcripts Alignment to a Reference) HISAT2, and so on depending on experimental design and research objectives. Commonly used alignment tools are BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) and Bowtie 2 and BLAST. Even if the alignment output in the form of a text-based Sequence Alignment Map (SAM) file is available, in NGS Binary Alignment Map (BAM) files are preferred because it is more compact and contains all the base call alignments to the reference sequences. The alignment of the sequence are visualized by uploading BAM or SAM files to specific genome browser such as Integrative Genomic Viewer (IGV). Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, mutations and other errors, overlaps called as pileups in the reads were determined from the sequence.

3. Variant Calling for DNA sequencing: This step is important to identify genetic variants including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions and deletions (indels), inversions, translocations, and structural variations with single base substitutions, from the completely aligned DNA sequence reads when compared to the reference genome. GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit), SAMtools, and FreeBayes are examples of popular variant calling algorithms. After identifying the variants in the sequence, annotation tools are used to study functional information of variants such as affected genes, amino acid variations, and many others. After sequence alignment, the mutated genes which do not match with reference genome are listed in a Variant Call Format (VCF) file. Common genetic variations included structural rearrangements chromosomal abnormalities, and copy number variations (CNVs). In case of RNA sequencing, after identifying the mutated sequences, the step followed gene counting and differential expression of data in Tab Separated Values (TSV) files representing sample details, genes, amplicon IDs, raw counts and normalized counts.

4. Gene Expression Quantification (for RNA sequencing): This step identifies expression levels of genes such as differentially expressed genes and gene regulation in biological data using RNA sequencing methods. Normalization methods such as RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads) or TPM (Transcripts Per Million) can be used to compare the expression levels of genes between different samples. Using visualization tools such as heatmaps, volcano plots, and scatter plots, gene expression data can be displayed for studying biological significance.

5. Post-processing and Annotation: Post-processing steps are performed to improve the quality and interpretability of the results. Databases like dbSNP, ClinVar, and COSMIC are commonly used for variant annotation. This step helps to identify biological pathways and functional genes by gene expression changes or variant occurrences in each sequence.

6. Downstream analysis: This step depends on primary data obtained from read alignment, variant calling, gene expression quantification, and annotation for providing meaningful insights into experimental data. It uses bioinformatics tools, statistical methods, and visualization processes for extracting high-throughput sequencing data. This step is crucial for identifying potential targets for therapeutic approaches.

7. Integration with Biological Knowledge: This step links the results including annotated genes, genetic variants, differentially expressed genes, genomic locations, protein domains, biological pathways, and many others to generate biologically meaningful interpretations of their results.

Figure 1: NGS data analysis pipeline Adapted from: Kumaran, M., Subramanian, U., & Devarajan, B. (2019). Performance assessment of variant calling pipelines using human whole exome sequencing and simulated data. BMC bioinformatics, 20(1), 1-11.