Tailoring Microstructure With Various Heat Treatments (Annealing, Normalizing, and Quenching)

1 Introduction

Heat Treatment refers to a process of subjecting a metal/alloy to heat with an intention of tuning its microstructure, and hence its properties. A heat treatment of an alloy involves three basic steps: heating, soaking, and cooling at desired rates. Heat treatments are usually carried out to alter the microstructure of metals and alloys to tune their properties for various applications. Heat treatment can also alter certain manufacturability objectives, such as improving machining, enhancing formability, and restoring ductility after a cold working operation. The method chosen depends on the desired characteristics of the material. Steels are the most widely used engineering material as their properties can be varied widely by employing suitable heat treatment schedules. Figure 1 demonstrates different types of heat treatments.

2 Annealing

Annealing is a heat treatment process generally used to increase the ductility and reduce the hardness of steel to make it more workable (the material can be cold worked for larger strains without fracture) by producing soft, coarse pearlite in steel by austenitizing, then furnace cooling. The process involves the following steps:

a. Heating the steel above its A3 temperature, it exists as single-phase austenite.

b. Keeping the material at the above-mentioned temperature for a definite time to achieve homogenous austenitisation.

c. Furnace cooling of the material to make it nearly stress-free (by reducing the defects and internal stresses of the material), and the phases reach their equilibrium compositions and phase fractions as per the phase diagram.

Annealing also comprises different types, which are discussed below:

- Full annealing

The purpose of this heat treatment is to obtain a material with high ductility. A microstructure with coarse pearlite (i.e., pearlite having high interlamellar spacing) is endowed with such properties. The range of temperatures used is given in the figure below. The steel is heated above A3 (for hypo-eutectoid steels) & A1 (for hyper-eutectoid steels) → (hold), → then the steel is furnace cooled to obtain Coarse Pearlite. Coarse Pearlite has low (↓) Hardness but high (↑) Ductility. The heating is not done above Acm for hyper-eutectoid steels to avoid a continuous network of pro-eutectoid cementite along prior Austenite grain boundaries.

- Recrystallization annealing

During any cold working operation (say cold rolling), the material becomes harder (due to work hardening) but loses its ductility. This implies that to continue deformation, the material needs to be recrystallized (wherein strain-free grains replace the ‘cold worked grains’). Hence, recrystallization annealing is an intermediate step in (cold) deformation processing. To achieve this, the sample is heated below A1 and held there for sufficient time for recrystallization.

- Stress relief annealing

Due to various processes like quenching (differential cooling of surface and interior), machining, phase transformations (like martensitic transformation), welding, etc., the residual stresses develop in the sample. Residual stress can lead to undesirable effects like the warpage of the component. The annealing is performed below A1, wherein ‘recovery’ processes are active (Annihilation of dislocations, polygonization).

- Spheroidization annealing

This heat treatment given to high-carbon steel requires extensive machining before final hardening & tempering. The main purpose of the treatment is to increase the ductility of the sample. Like stress relief annealing, the treatment is done just below A1. Long-time heating leads cementite plates to form cementite spheroids. The driving force for this (microstructural) transformation is the reduction in interfacial energy.

3 Normalizing

Normalizing is a heat-treatment process often used to provide grain size and composition uniformity throughout bulk material. It is a simple heat treatment obtained by austenitizing and air cooling to produce a fine pearlitic structure. Fine pearlite has a reasonably good hardness and ductility. The process involves the following steps:

- Heating the steel to above its A3 temperature.

- Keeping the steel at the above-mentioned temperature for a definite time to achieve homogenous austenitisation.

- Cooling the material in air (termed air-cooling) to get uniform and relatively fine-grained distribution.

In hypo-eutectoid steels normalizing is done 50° C above the annealing temperature. In hyper-eutectoid steels normalizing done above Acm → due to faster cooling cementite does not form a continuous film along grain boundaries. Normalizing produces higher amount of pearlite than annealing in a steel of same carbon content. Normalizing gives harder and stronger steel, but with less ductility for the same composition than full annealing. It also reduces the segregation in the castings and forgings.

4 Hardening and quenching

Hardening process often results in an increase in the level of hardness, producing a stronger material. The process involves the following steps:

- Heating the steel to above its A3 temperature.

- Keeping the steel at the above-mentioned temperature for a definite time to achieve homogenous austenitization.

- Quenching the steel in water or oil causes the soft initial material to transform into a much harder, stronger structure (martensite). The Martensite produced is hard and brittle, and the tempering operation usually follows hardening. This gives a good combination of strength and toughness.

Often, the hardened material is very brittle and cannot be used without tempering to improve its toughness.

5 TTT Diagram

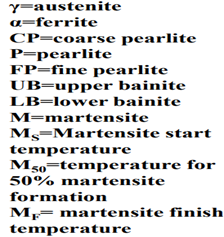

The TTT diagram stands for the “time-temperature-transformation” diagram and is known as the isothermal transformation diagram, which provides important details related to the kinetics of isothermal transformations. Davenport and Bain were the first to develop the TTT diagrams for the eutectoid steels, which were modified later by Cohen. Salt bath techniques following dilatometry, electrical resistivity method, magnetic permeability method, in-situ X-ray and neutron diffractions, acoustic emission, thermal measurement techniques, and density measurement techniques are some known methods for obtaining the TTT diagrams for different types of steels. Among all of them, the salt bath is the most common and well-established method for determining the TTT curves for steels. Figure 2 shows different TTT diagrams for hypoeutectoid, eutectoid, and hyper-eutectoid steels. Austenite transformation is plotted against temperature vs. time on a logarithm scale to obtain the TTT diagram. The shape of the diagram looks like either S or C. Usually, for hypo eutectoid steels, heat treatment is started from the temperature between A1 and A3 temperatures (A1 and A3 are the intercritical temperatures). Coarse pearlitic microstructure forms closer to A1 due to low nucleation rate and higher growth rates, whereas at higher cooling or lower temperatures fine pearlite results and very fine pearlite results at the nose of the TTT curves. Close to the eutectoid temperature, the undercooling is low, so the driving force for the transformation is small. However, as the undercooling increases, transformation accelerates until the maximum rate is obtained at the “nose” of the curve. Below this temperature, the driving force for transformation continues to increase, but the reaction is now impeded by slow diffusion. This is why the TTT curve takes on a “C” shape with the most rapid overall transformation at some intermediate temperature. After cooling from the austenite and holding the sample below the TTT curve for a sufficient time causes the bainitic transformation within the sample to forms a bainite phase. Bainite is also found in two different types: upper bainite and lower bainite. Upper bainite forms at higher temperatures and closer to the nose of the TTT curve, whereas lower bainite forms at lower temperatures but above Ms temperatures. Cooling the metastable austenitic phase sufficiently faster allows the formation of the martensite phase via athermal transformations (time-independent transformation). This temperature is denoted as Ms temperature or martensite start temperature. Below Ms, while metastable austenite is quenched at different temperatures amount of martensite increases with decreasing temperature and does not change with time. The temperature at which 99% martensite forms is called martensite finish temperature or MF.

Various information that can be extracted from the TTT diagram includes

● Nature of transformation-isothermal or athermal (time-independent) or mixed

● Type of transformation-reconstructive or displacive

● Rate of transformation

● Stability of phases under isothermal transformation conditions

● Temperature or time required to start or finish transformation

● Qualitative information about size scale of product

● Hardness of transformed products