The Study of Phase Change

Theory

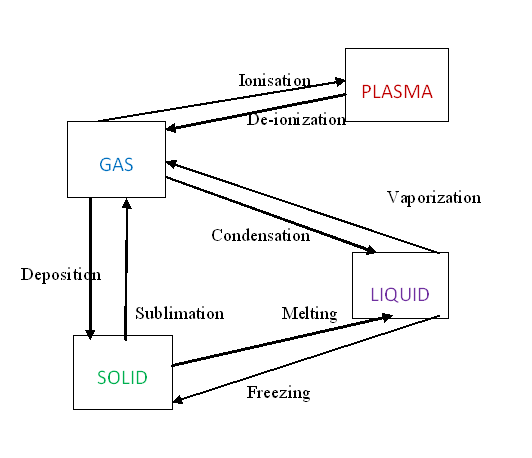

The term phase change—also known as change of state—refers to the transformation of a substance from one physical state (solid, liquid, or gas) to another. This process always involves the transfer of heat energy, but interestingly, the temperature of the substance remains constant during the transition.

When a solid is heated, the supplied thermal energy increases the kinetic energy of its molecules, raising its temperature. However, at the melting point, additional heat energy is no longer used to increase kinetic energy. Instead, it is used to partially overcome the cohesive forces between molecules, enabling the transition from solid to liquid. A similar mechanism occurs when a liquid transitions to a gas during vaporization, requiring energy to overcome intermolecular attractions.

During a phase change, the temperature of the substance remains constant because the energy supplied is entirely used for altering the molecular arrangement—not for increasing molecular motion. As a result, there is no rise in temperature until the entire substance has completed the phase transition.

The amount of heat energy absorbed or released during a phase change at constant temperature is referred to as the latent heat. When this energy is measured per unit mass of the substance, it is known as the specific latent heat. The specific temperature at which a phase change occurs—such as the melting point (solid to liquid) or boiling point (liquid to gas)—is characteristic of the substance and remains constant during the transition.

The process, phase transition is governed by Newton's law of cooling, which states that,

"The rate of change of temperature of an object is proportional to the difference between its own temperature and the temperature of its surroundings."

where , is the temperature of the object, is a positive constant, is the temperature of the surroundings.

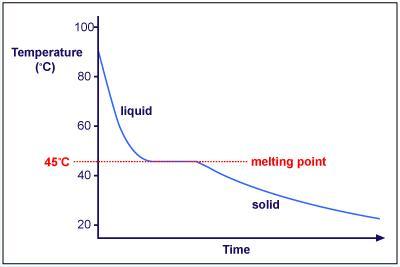

By studying the phase change of a substance from solid to liquid, one can determine the melting point, latent heat of fusion etc of the substance. In order to understand more about the theory of phase change, consider a sample cooling curve for a substance with a melting point of .

The flat portion of the graph represents the phase change from liquid to solid at the constant melting temperature . The two curved portions represent cooling of the liquid plus the tube (left) and cooling of the solid plus the tube (right). These cool according to Newton’s law of cooling,

where is the temperature of the sample, is room temperature, and is a positive constant.

The heat loss rate of the liquid plus the boiling tube is likely to be the same as the heat loss rate of the solid plus the tube for a given temperature difference

The specific heat of the material undergoing phase change is, however, unlikely to be the same for the liquid () and the solid () phases. Thus we have

and

where upon it can be seen that the cooling constants in the liquid (l) and solid (s) phases are related by the equation

These cooling constants can be estimated by using the graph to estimate the time te taken for the material plus the tube to cool to 1/e of their starting temperature above room temperature. Then since the solution to the Newton’s law of cooling differential equation is

we have