Microstructure of Various Cast Irons and Quantification

1 Introduction

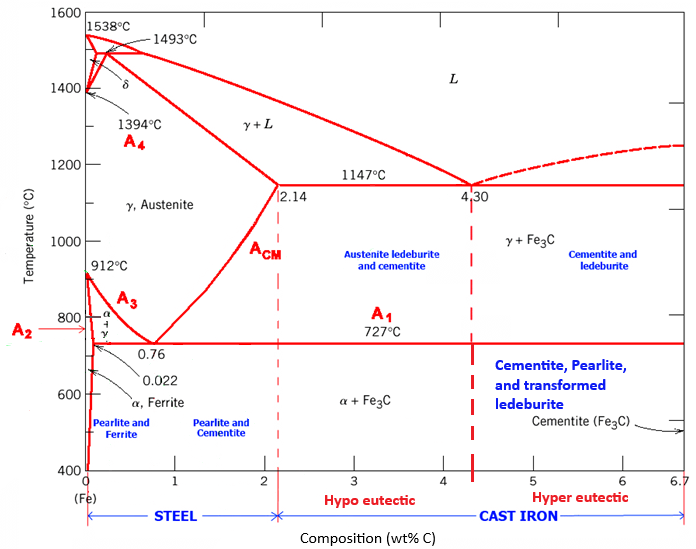

Referring to the iron-carbon phase diagram of the previous virtual lab (experiment 6), Cast iron is primarily composed of iron (Fe) with a significant proportion of carbon (C > 2.1 wt.%) and other alloying elements. The microstructure of cast iron is typically characterized by the presence of graphite flakes or nodules embedded in the ferrite matrix and/or cementite. Depending on the processing parameters, the microstructure can vary significantly, leading to different types of cast iron, including grey iron, white iron, and ductile iron.

2 Different types of phases and microstructural evolution in cast iron:

Different types of microstructural phases are found in cast iron. These include cementite, austenite, ledeburite, and transformed ledeburite. Austenite is a high-temperature FCC phase. Cementite, also termed iron carbide, is a compound of iron and carbon with an orthorhombic crystal structure. Ledeburite is an eutectic phase mixture of austenite and cementite, and ledeburites contain a mixture of pearlite and cementite, known as transformed ledeburite. Three different regions on the cast iron part of the phase diagram are hypoeutectic regions in the range of (2.1-4.3 wt.%C), a 100 % ledeburite forms via eutectic reaction at 4.3 wt.%C at eutectic point, and finally (4.3-6.7) wt.%C range forms hyper eutectic region. During the microstructural evolution, different types of microstructures evolve in all three other regions of the cast irons. In the case of hypoeutectic regions during cooling, starting from the liquid region, a mixture of liquid and austenite are found initially, where dendrites of austenite form, which then transforms into a mixture of austenite and ledeburite after passing the eutectic reaction line, and finally converts into a microstructure of pearlite and transformed ledeburite. At 4.3 wt.%C, a eutectic mixture of austenite and cementite forms 100% pure eutectic ledeburite, which finally converts into transformed ledeburite after passing the eutectic regions. Ultimately, in the case of the cooling of the hyper-eutectic region, the liquid evolution of primary cementite further forms a mixture of ledeburite and cementite after passing the eutectic region and a mixture of cementite and transformed ledeburite after crossing the eutectoid region.

Gray Iron is one of the most common forms of cast iron. Its microstructure consists of graphite flakes dispersed throughout a matrix of ferrite and pearlite. The graphite flakes provide excellent lubrication and vibration-damping properties, making grey iron suitable for applications like engine blocks and pipes.

2.2 White Iron

White iron has a different microstructure, with most carbon present as cementite (Fe₃C) rather than graphite. This results in a white, hard, and brittle material. White iron is exceptionally wear-resistant, making it suitable for grinding balls and crusher liners.

2.3 Ductile Iron

Ductile iron, also known as nodular or spheroidal graphite iron, features graphite nodules rather than flakes in its microstructure. This nodular graphite increases ductility and toughness compared to grey or white iron. Ductile iron is used in applications requiring a combination of strength, ductility, and wear resistance, such as automotive components and pipes.

2.4 Malleable Iron

White cast iron heat treated at around 920oC followed by slow cooling to modify its microstructure.The resultant iron is Malleable Iron. Its microstructure consists of a ferrite matrix and tempered carbon. The graphite rosettes are unique features of the microstructure, making it distinguishable from the other microstructures. They have mechanical properties intermediate between grey cast iron and ductile iron. This makes its applications specified to the areas where toughness, machinability, ductility, and malleability are required. It is used as an alternative to steel and in other applications of pipe fittings washers.

2.5 Compacted Iron

Compacted cast iron a unique identity due to the vermicular-shaped graphite's presence, making it a semi-ductile iron. It is specifically used in areas where higher strength and lower weights than cast irons become an essential entity. They find applications in the manufacturing of diesel engine blocks.

3 Manufacturing Processes:

The manufacturing process strongly influences the microstructure and properties of cast iron. The key manufacturing processes for cast iron include:

3.1 Melting and Casting

The process begins with melting iron and other alloying elements in a furnace. Once molten, the alloy is poured into molds to form the desired shape. The cooling rate during casting plays a significant role in determining the microstructure. Slow cooling promotes the formation of graphite flakes, while rapid cooling favors the development of nodular graphite.

3.2 Alloying

Alloying elements, such as silicon (Si), manganese (Mn), and sulfur (S), are added to control the microstructure and properties of the cast iron. For example, Silicon promotes graphite formation, while manganese enhances strength and ductility.

3.3 Heat Treatment

Heat treatment processes like annealing and quenching refine the microstructure and enhance properties. Annealing can soften the material by converting cementite into graphite, while quenching can increase hardness by promoting martensite formation.

4 Properties of Cast Iron:

Cast iron exhibits a wide range of properties, making it suitable for diverse applications.

4.1 High Strength

Cast iron has excellent compressive strength, making it ideal for structural components.

4.2 Good Thermal Conductivity

It conducts heat efficiently, making it suitable for cookware and engine components.

4.3 Wear Resistance

White iron and some alloyed cast irons are highly wear-resistant, making them valuable for abrasive environments.

4.4 Damping Capacity

Gray iron's graphite flakes provide exceptional vibration damping, making it useful in machinery and automotive applications.

4.5 Corrosion Resistance

Some cast iron types are corrosion-resistant due to forming a protective oxide layer.

4.6 Machinability

Cast iron is relatively easy to machine, making it versatile for various applications.

5 Factors Influencing Properties:

Several factors influence the properties of cast iron:

5.1 Microstructure

The type and distribution of graphite and other phases within the microstructure greatly impact properties.

5.2 Alloying Elements

Adding alloying elements can modify hardness, strength, and corrosion resistance.

5.3 Heat Treatment

Heat treatment can tailor the material's properties to specific applications.

5.4 Cooling Rate

The cooling rate during casting affects the microstructure, with slower cooling favoring graphite formation.

5.5 Manufacturing Process

Different manufacturing processes, such as grey or ductile iron casting, result in distinct microstructures and properties.

In short, cast iron's microstructure and properties result from a delicate balance between alloy composition, manufacturing processes, and heat treatment. Its versatility, from wear-resistant white iron to vibration-damping grey iron and tough ductile iron, makes it indispensable in various industries. Understanding the microstructure-property relationships of cast iron is crucial for selecting the right material for specific applications and optimizing its performance. As technology advances, the development of new cast iron alloys and manufacturing techniques continues to expand the possibilities for this remarkable material.

6 Important alloying elements and their functions:

| Alloying elements | Range of percentages | Important functions |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfur | 0.33 | Improves machinability, reduces weldability and ductility |

| Phosphorus | 0.12 | Improves machinability and reduces impact strengths at lower temperatures. |

| Silicon | 1.5 – 2.5 | Removes oxygen from molten metal, improves strength and toughness, increases hardenability magnetic permeability |

| Manganese | 0.5 – 2.0 | Increases hardenability and reduces adverse effects of Sulphur |

| Nickel | 1.0 – 5.0 | Increases toughness and impact strength at lower temperatures |

| Chromium | 0.5 – 4.0 | Improves resistance to oxidation and corrosion, increases high-temperature strength |

| Molybdenum | 0.1 – 0.4 | Improves hardenability, enhances the effects of the other alloying elements, eliminates temper embrittlement, and improves red hardness and wear resistance. |

| Tungsten | 2.0 – 3.0 | Improves hardenability, enhances the effects of the other alloying elements, eliminates temper embrittlement, and improves red hardness and wear resistance. |

| Vanadium | 0.1 – 0.3 | Improves hardness, increases wear and fatigue resistance |

| Titanium | < 1.0 | Improves strength and corrosion resistance |

| Copper | 0.15 – 0.25 | Improves strength, corrosion resistance and hardness |

| Aluminium | 0.01 – 0.06 | Removes oxygen from molten metal |

| Boron | 0.001 – 0.05 | Increases hardenability |

| Lead | < 0.35 | Increases machinability |