Sectioning, Mounting, Grinding, Surface Preparation, Technique for Polishing and Etching of Materials (including Electropolishing, tint etching etc.)

Ceramography is the study of the microstructure of ceramic materials using microscopy. It involves the art and science of preparing, interpreting, and analyzing microstructures in ceramics to better understand their behavior and performance. This method is widely used in various industries, including aerospace, electronics, biomedical, and structural applications. It is essential for quality control, failure analysis, and research into advanced ceramic materials.

• A well-prepared ceramographic specimen should be:

• A representative sample that accurately reflects the microstructure of the bulk material.

• Sectioned, ground, and polished to minimize surface damage and deformation, ensuring the true microstructure is revealed during etching.

• Free from polishing scratches, pits, and contamination to avoid misinterpreting the microstructure.

• Flat and well-polished to allow accurate examination under an optical microscope, SEM, or other advanced characterization techniques.

Preparing ceramic samples for ceramography involves several critical stages to ensure high-quality microstructural analysis. The major stages include-

• Sawing

• Mounting

• Grinding

• Polishing

• Etching

• Microscopy and Analysis

Sample preparation : The first step in ceramography involves the careful preparation of samples for microscopic analysis. This includes sawing, mounting, grinding, polishing, and etching the ceramic specimens to reveal their internal microstructure without inducing artifacts.

Precision cutting tools, diamond saws, and abrasive slurries are commonly used for sectioning ceramics, ensuring minimal damage to the material’s structure. Mounting the samples in resin or epoxy provides stability during subsequent grinding and polishing stages.

1 Sawing :

Sawing is performed to extract a representative sample from a ceramic component for polishing and microscopic examination or to isolate a specific region of interest. This process must be carried out carefully to minimize damage, such as cracks or surface flaws, ensuring the integrity of the sample for further analysis in ceramography.

Saw the ceramic component with a water-cooled, low-density, metal-bonded diamond wafering blade on a high-speed cut-off machine, as shown in Figure. A resin-bonded diamond blade may be advantageous for some specimens. Use a load of approximately 5 to 10 N (500 to 1000 gf) and a blade rotation rate of 2000 to 5000 rpm for dense ceramics. Use 1 N and 500 rpm for most refractories, concrete, and semiconductors. A low-speed saw that uses oil or kerosene as the coolant and lubricant can also be used, although the cutting rate can be excruciatingly slow for dense ceramics at 500 rpm. Both types of saws are available from several of the manufacturers listed in Appendix B. Feed the component into the blade (or the blade into the component) slowly but steadily to avoid jagged sawed surfaces. Remove the burrs, if necessary, with a coarse (400-grit or 45 µm) diamond grinding wheel.

Sawing should be performed carefully to minimize damage to the specimen, including overheating, dislocations, deformation twinning, and surface cracking. While ceramics are generally less prone to overheating than other materials, the use of a liquid coolant is essential. The coolant must be chosen carefully to ensure the ceramic remains insoluble in it.

If an oily lubricant is used, clean the specimen in warm water with a detergent like Ivory, Micro-90, etc. Use distilled or deionized water if tap water is too hard. Ensure the specimen is not water-soluble before cleaning.

2 Mounting :

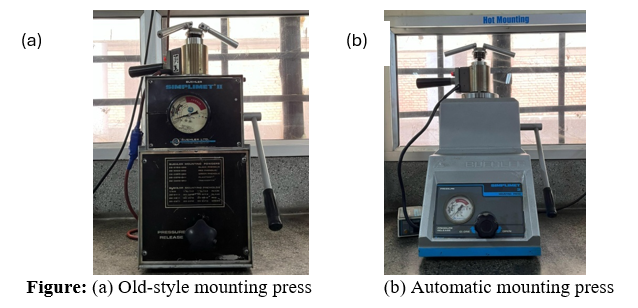

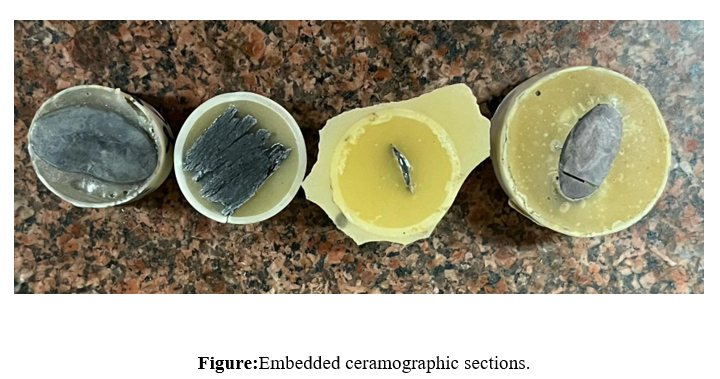

Ceramic samples can be mounted in two ways. Dense ceramics are best mounted using powdered resins that polymerize under uniaxial compression, often containing fillers to enhance properties. Older manual presses function like car jacks, while modern automated presses use water cooling and compressed air for faster processing. Fragile, porous, or friable ceramics are better suited for castable liquid resins, which polymerize in the presence of a catalyst or hardener. The mounting of ceramics, such as alumina (Al₂O₃), Zirconia (ZrO₂), and Silicon Carbide (SiC), can be achieved by either cold or hot mounting. In cold mounting, samples are embedded in epoxy or acrylic resin and cured at room temperature or slightly heated (~30–40°C), suitable for all three ceramics to avoid thermal stress. In hot mounting, samples are pressed in thermosetting resin like bakelite at around 180°C and 250–300 bar pressure for a few minutes. While hot mounting gives strong support, care is needed to avoid cracks, especially in brittle materials like SiC.

2.1 Compression Mounting :

Compression mounting is a technique used to encapsulate ceramic or metallic specimens in a hardened resin for easier handling during microstructural analysis. This method is ideal for dense, non-porous materials that can withstand heat and pressure without degradation. It can be done two ways-

• Compression Mounting-Automatic Mounting Press

• Compression Mounting-Hydraulic Mounting Press.

2.2 Castable Mounting (Cold mounting) :

Castable liquid resins are used for mounting fragile and porous ceramics, filling voids in refractory bricks, mineral sections, and microelectronic devices. A vacuum chamber aids in mold filling, while low-stress curing preserves delicate structures. Fragile ceramics can be mounted before sawing to prevent damage.Also called cold mounting, this method involves an exothermic polymerization reaction, reaching ~120°C, lower than the 150°C of compression mounting. Unfilled resins have low abrasion resistance, which can be improved by adding ceramic particles.

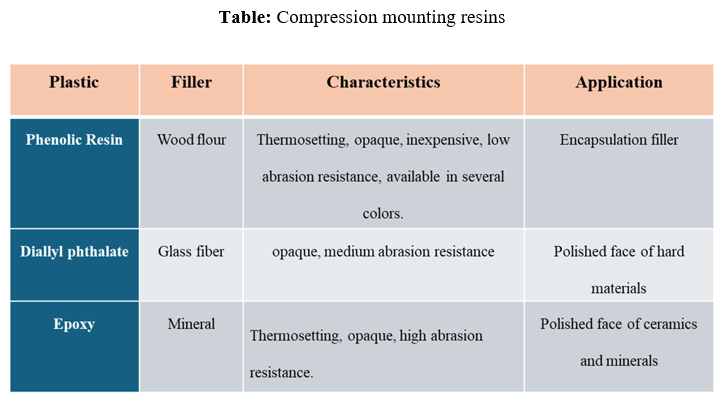

The below table provides information on different compression mounting resins, their fillers, characteristics, and applications.

3 Grinding :

Grinding is an essential step in the preparation of ceramic samples for microstructural analysis, ensuring that the specimen achieves a flat, smooth surface suitable for further processing. Due to the inherently brittle and hard nature of ceramics, improper grinding can introduce microcracks, chipping, and other defects that may obscure true microstructural features. To minimize such damage, specialized abrasive techniques are employed, using a sequential grinding approach with silicon carbide (SiC) abrasive papers.

The grinding process typically begins with coarse grit (~240) to remove major surface irregularities and residual deformations from sectioning. It then progresses through medium (400–600 grit) and fine (800–1200 grit) abrasives to refine the surface gradually. The selection of grit size depends on the material hardness and required finish, ensuring that excessive material removal is avoided while effectively eliminating scratches and damage.

To control heat generation and prevent thermal stress, water or alcohol-based lubricants are used during grinding, aiding in material removal while reducing the risk of surface contamination. Consistent application of the correct pressure and rotation speed is also critical in maintaining uniformity and preventing localized damage.

Properly executed grinding is vital as it directly impacts the efficacy of subsequent polishing and etching stages. A well-ground ceramic sample will exhibit minimal defects, allowing for high-resolution microscopic examination using optical and electron microscopy techniques.

4 Polishing :

Polishing is a crucial step in ceramography to achieve a smooth, scratch-free surface for microscopic examination. After grinding, the ceramic sample undergoes a series of polishing stages using progressively finer abrasives. Diamond suspensions (6 µm, 3 µm, and 1 µm) are commonly used, followed by a final polish with colloidal silica (0.05 µm) to remove any residual scratches and enhance contrast. The polishing process must be carefully controlled to prevent surface damage, such as pull-outs or smearing, which can obscure microstructural features. Proper lubrication and controlled force ensure a high-quality finish suitable for optical and electron microscopy.

5 Etching :

The etching of ceramic samples is crucial in microscopy experiments to reveal their microstructural features, such as grain boundaries, phases, and defects. Unlike metals, ceramics are often more chemically inert, making their etching process more challenging and requiring specialized etchants tailored to the material composition. The primary purpose of etching in ceramics is to enhance contrast under an optical or electron microscope by selectively dissolving certain phases or inducing differential surface roughness. This allows researchers to study grain morphology, phase distribution, and structural integrity, which are essential for understanding the material's mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. Proper etching ensures accurate interpretation of the microstructure, aiding in quality control, failure analysis, and material development.

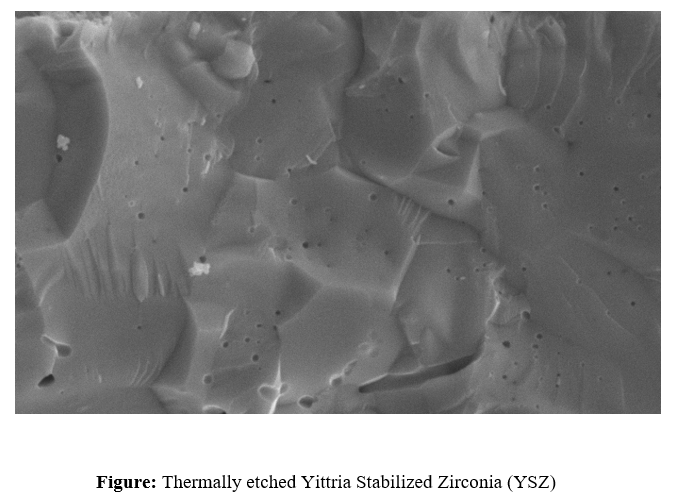

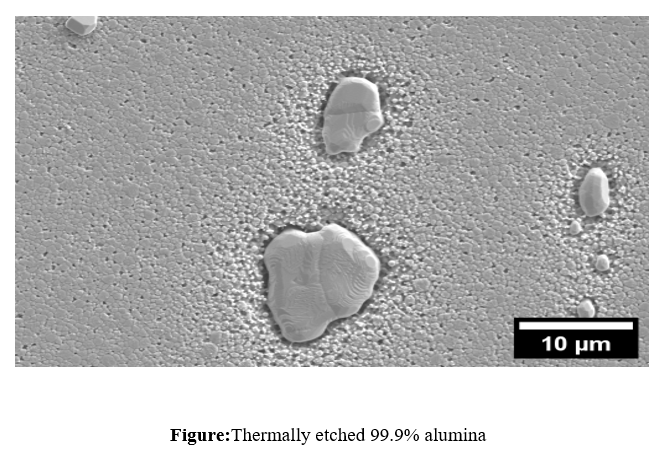

Etching reveals and delineates grain boundaries and other microstructural features that are not apparent on the as-polished surface. The two most common types of etching in ceramography are selective chemical corrosion and a thermal treatment that causes relief. As an example, alumina can be chemically etched by immersion in boiling concentrated phosphoric acid for 30–60 s, or thermally etched in a furnace for 20–40 min at 1,500 °C (2,730 °F) in air. The plastic encapsulation must be removed before thermal etching. The alumina in the below Figure was thermally etched. Al2O3 and Al2O3-MgO are etched through thermal etching in air, while ZrO2 requires DI water and H2SO4 for effective etching. SiC, being highly chemically resistant, is etched using a molten salt mixture of NaHCO3and KHCO3. WC can be etched using HCl or 30% H2O2, allowing phase contrast enhancement. Si3N4 undergoes thermal etching in high-purity nitrogen to prevent oxidation. ZrB2 is etched using nitric acid (HNO3) and hydrofluoric acid (HF) to highlight grain boundaries, while TiB2 requires lactic acid (2-hydroxypropanoic acid) for controlled surface etching. Each method is tailored to the chemical stability and microstructure of the respective ceramic for precise characterization.

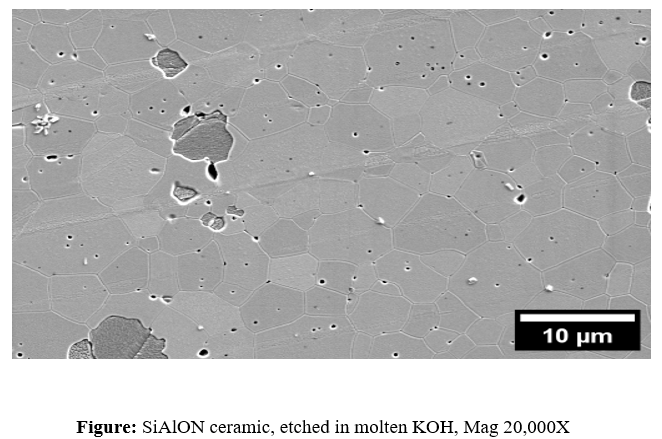

Etching of ceramic samples can be broadly classified into chemical etching, thermal etching, and plasma etching, each tailored to specific materials and analysis requirements. Below are the different types of etching techniques along with common etchants used for ceramic materials-

5.1 Chemical Etching :

Chemical etching is a widely used technique in ceramics to enhance the visibility of microstructural features such as grain boundaries, phases, and defects under a microscope. Since ceramics are typically chemically inert, specialized etchants are required to selectively dissolve certain phases or induce surface roughness. The process involves immersing the polished ceramic sample in a suitable chemical reagent that reacts with specific components of the material, thereby revealing structural details.

Different ceramics require different etchants due to their varying compositions. For instance, alumina (Al2O3) is often etched using hot phosphoric acid (H3PO4), while zirconia (ZrO2) can be etched with hydrofluoric acid (HF) or hydrochloric acid (HCl) mixed with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Silicon-based ceramics like SiC and Si3N4require stronger etchants such as molten alkalis (NaOH or KOH) or fluorinated acids. The etching duration, temperature, and concentration of the etchant must be carefully controlled to prevent excessive material removal or unwanted damage.

5.2 Thermal Etching :

Thermal etching is a technique used to reveal the microstructure of ceramic materials without the use of chemical reagents. It involves heating the polished ceramic sample to a temperature slightly below its sintering point, allowing surface diffusion and grain boundary grooving to occur. This controlled heating process enhances the visibility of grain boundaries, phase distribution, and porosity under a microscope. Unlike chemical etching, thermal etching does not introduce artificial defects or contamination, making it particularly useful for studying intrinsic microstructural features. It is essential for ceramics that are chemically resistant or prone to excessive dissolution in chemical etchants, such as alumina (Al2O3), silicon carbide (SiC), and zirconia (ZrO2).