Effects of Lubrication

As a result of the friction between tribological surfaces, there is a local increase in temperature, particularly at the asperities. Frictional heating exacerbates the rate of material wear. Therefore, it is essential to reduce frictional heating. This can be accomplished by utilizing materials with superior transport properties (such as higher thermal conductivity). Nevertheless, for every application, the materials are predetermined, and we can do little to improve their thermal properties. Lubrication is another effective method for reducing frictional heat.

Thus, the objective of lubrication is summarised below.

- To reduce the wear at the contacting surfaces

- To reduce the friction at the contacting surfaces

- To transfer heat away from the sliding surfaces

- To carry away wear debris from the tribo-contacts (e.g., in case of abrasive wear)

The lubricant adheres to the contacting surfaces and forms a lubricating film that keeps the surfaces apart, thereby reducing friction and wear. The lubricant film thickness (h) can be related to its viscosity (η), sliding speed (v), and the load experienced at the contact surfaces (F) as follows:

One of the primary objectives of lubrication is to reduce friction. However, based on equation (1), the lubricant must have specific properties such as low shear-strength, high viscosity, and high thermal conductivity to prevent frictional heating. Additionally, the lubricant must be chemically inert to provide corrosion protection. However, one of the primary goals of lubrication is to reduce friction.

A lubrication parameter or film parameter, λ, which is described using lubricant-film thickness and surface roughness as follows, is frequently used to measure the effectiveness of lubrication.

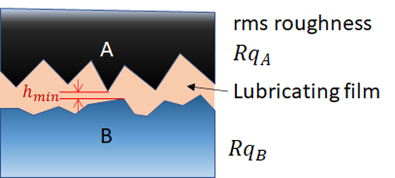

where hmin is the minimum film thickness, and RqA and RqB are the root mean square roughness of the contacting surfaces A and B, respectively (as shown in the Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Two contacting surfaces A and B having a lubricant-film in between them.

Types of Lubrication

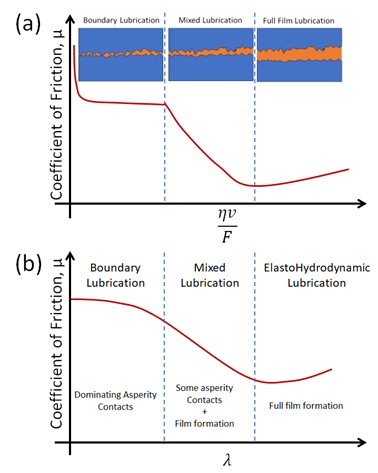

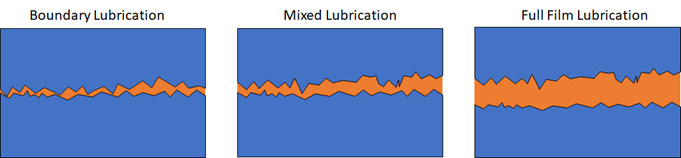

There are three types of lubrication: Boundary Lubrication (BL), Mixed Lubrication (ML) and Full film Lubrication (FFL). The Fig. 2 is schematic demonstrating these lubrication types.

Fig. 2: Schematic showing types of lubrication. Notice the lubricant film thickness (without an external pumping agency) formed between the two tribological surfaces.

The full film lubrication is classified into further two categories based on the relative motion of sliding bodies. Hydrodynamic lubrication occurs when two surfaces fully separated by liquid film are in sliding motion, while elastohydrodynamic lubrication occurs when surfaces are in rolling motion.

Full-film lubrication

As mentioned earlier, even the most polished surfaces have asperities. Thus, the lubricating film must be thicker than the length of the asperities for the lubricant to form a full-film. This lubrication best protects surfaces and is also the most preferred.

Boundary lubrication

When two tribosurfaces are too close to one another, and there is a relative motion, the surface asperities dominate the contact. This condition is known as boundary lubrication. This type of lubrication is not ideal because it increases wear rates, generates high levels of frictional heat, and has other adverse effects.

Mixed Lubrication

Mixed lubrication is a state that is a mix of hydrodynamic lubrication and boundary lubrication. In this state, a lubricating film keeps the main surfaces apart, but asperities on surfaces can still make contacts with each other.

These lubrication conditions can be understood well using Stribeck curve and using a plot of coefficient of friction (µ) with film parameter (λ), as shown in the following figures.